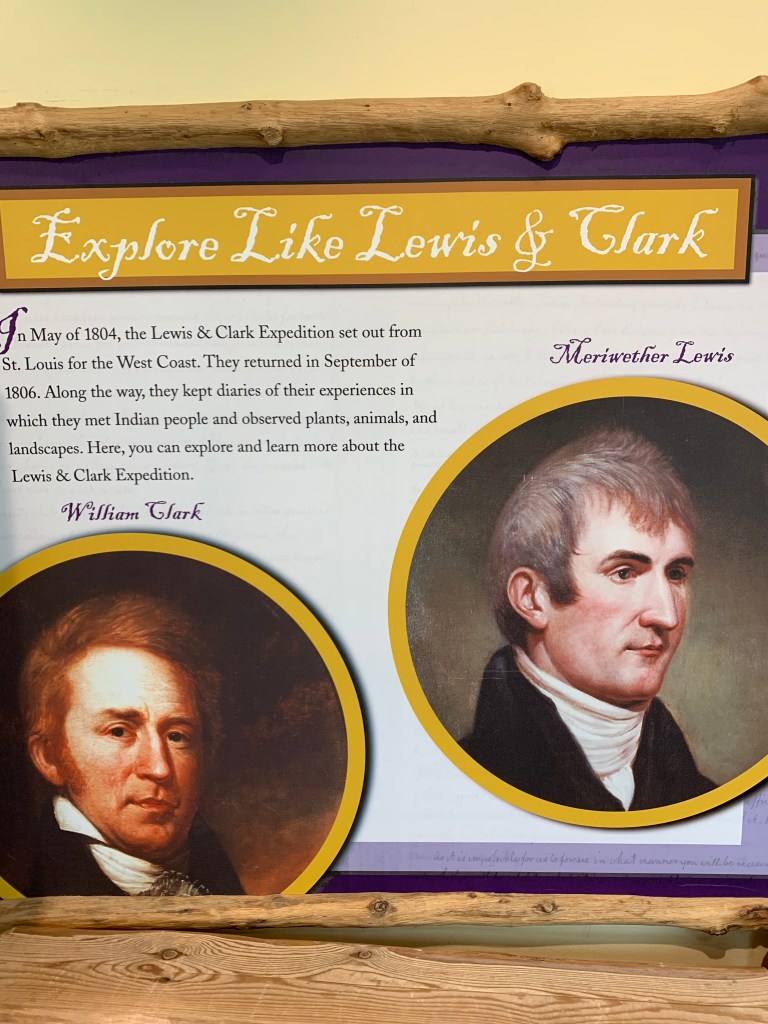

There were acts of undaunted courage in the Gorge, and then there were acts of undaunted clean up. First, in 1803 Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery, including Lewis’ Newfoundland Seaman, paddled across the country, then down the Columbia to the Pacific, then returned to DC to tell Jefferson the story in 1806. Then the Gorge opened up to white settlers, not just trappers and Natives. They led tough lives. Edward Crate and his wife Sophia had 14 children and 1000 sheep. They lost all their sheep in 1861. George D. Evans, born in Illinois, died in Wasco, OR in 1888 at age 25. His tombstone, pictured above, includes five words: “Not lost but gone home.”

We hiked the Mosier Plateau on the dry eastern side of the Gorge. The cornflowers colored the hillside blue. Locals swim in the pool below Mosier Falls, above. I much prefer a smaller, isolated waterfall to the marquis attractions along the Waterfall Scenic Corridor.

In Mosier Canyon we saw two Golden Eagles spiraling together in a double helix. A naturalist employed by the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center agreed with JG that it could have been a courtship display, called sky dancing. Bennett the Naturalist introduced us to a Kestrel named Hank. Hank cannot survive in the wild because he was kidnapped as a chick and his kestrel identity subverted with human imprint. He is now 14 years old, living on frozen mice and entertaining visitors with his preening and his tiny cries of “Kee-Ah! Kee-Ah!” I am uncomfortable seeing raptors in captivity, but knowing that Hank would die if released assuages my worry.

At the museum, I especially enjoyed learning more about vultures. They are easy to spot; they hunt smarter not harder. I have assigned them a verb, vulching. I have met the crafty and destructive black vultures in Everglades NP, where they contently prey on the rubber bits around car windows or on wiper blades. I enjoy Condor sightings in Pinnacles NP. And no hike is complete without a few turkey vultures, hanging out in a tree or circling overhead. Fun turkey vultures facts: They do not build nests, but lay eggs in rock and tree crevices. They do not have a voice box, but hiss and grunt to communicate. They can smell something dead within a five mile radius. That’d be like me smelling the candy apples on the Boardwalk from my backyard. When they feel threatened, they will vomit on their attackers, up to ten feet away. When I took a Women’s Self Defense Class, this method was also suggested to us, to fend off amorous advances. To cool themselves down and kill off any bacteria on their feet, vultures will urinate down their legs, a behavior known as “urohydrosis.” So if I pee myself, it is a hazmat detox shower if I’ve been thigh-deep in rotting carcass. That way the germs don’t land in my drinking water. We must all do what we can to protect vultures, because they are nature’s clean up crew.

Politics of settlement and conquest aside, I’m really glad I don’t have 14 children or 1,000 sheep!

Well, there is an admirable efficiency to the vulture’s defensive and hygiene practices. They’re making full use of every bodily function they’ve got.

LikeLike